We’ve moved to a monthly newsletter format for #TrackerTuesdays, so a new question SHOULD be posed every Tuesday, and answers SHOULD be published on the first Tuesday of every month. We apologize for the delay in publishing this one, in particular. We were swamped with trying to stay afloat during the lockdown and with finishing our new website for Tracker Mentoring (correspondence courses for trackers). It’s been a long 6 months in development for the launch of our first course, Introduction to Tracking in Southern Africa, but we’re very happy with the results. The website should be live by the end of this week!

Answer list: an ovenbird nest from Jonathan Shapiro in Vermont in the USA; an left ostrich track from Ngala Training Camp in the Greater Kruger area of South Africa; a left hind raccoon track from Wisconsin in the USA, a spotted hyena scat and tracks from Ngala Training Camp in the Greater Kruger area of South Africa; and a large bone moved by elephants from Ngala Training Camp in the Greater Kruger area of South Africa.

The art and science of tracking develops creative and critical thinking skills, and curiosity and empathy, which also help us to better understand our place as caretakers of this beautiful world. The full expression of tracking includes more than just identifying tracks and signs. It also includes the interpretation of behaviours from tracks and signs, and the following and finding of animals (or people) using tracks and signs. Following and finding, or trailing, also builds confidence and leadership qualities in individuals, and teamwork among groups. Tracking requires us to really see the environment, and each other, and to reconnect to fundamental systems of living, which include knowledge of self, and connection to community (including non-human communities) and land. Tracking IS original wisdom. It’s both ancient, and new. Our ancestors tracked animals for food, clothing, shelter, and better quality of life. Today, we push the frontiers of tracking forward by including technology and new discoveries. One of the best things about tracking is that the “book of nature” is so vast that we can never know it all. It’s always exciting and always humbling.

Tracker Tuesday, July 14, Bird Tracks and Signs

Our question today was from Jonathan Shapiro in Vermont in the USA. Who’s nest, and why?

An ovenbird nest photographed by Jonathan Shapiro in Vermont, in the USA.

Anne Marie Meegan (New England, USA) – Is it an Ovenbird’s nest? I’ve never seen one but have read descriptions…. it’s on the ground and looks like a beehive oven.

wildwoodpath (Trevanna Frost Grenfell, Maine, USA) – Ahhhhhhhh, so adorable!!! A bun in the oven! Reddish spots on white eggs about an inch long! Massive dome over a wee cavity! Dense debris! The only thing that makes me say not Ovenbird is all the grass… that doesn’t seem like their habitat. Love this photo regardless. I am not that great with nests but I thought of and rejected the ideas of these birds who sometimes make domed nests: Hermit Thrush (eggs more blueish), Winter Wren (usually in roots), Common Yellowthroat (good candidate but usually not so very domed). I’m here to learn so hoping to see other guesses that teach me new ideas! Thanks for these questions. Possibly more than one species involved?

schickchick21 (Stephanie Schick, Connecticut, USA) Whippoorwill? Main diet of ground beetles. I heard they don’t even make nests, but I don’t know much about them. Sadly, they’re really rare where I live these days. They don’t “make nests” like other birds, they lay on leaf litter. I see an egg on leaf litter. I don’t know what is adjacent to the egg on leaf litter though. The egg’s appearance DOES resemble a whippoorwill, and the surroundings ARE typical of the species. So, I’m now really eager to hear the answer.

Anne-Marie, Trevanna, and Stephanie were on the right track. The egg was predated. It was also photographed by Jon, so he moved it a bit. And there is definitely more than one species involved if you count who laid the egg (and made the nest) and that it was predated by something else.

OVENBIRD NEST DESCRIPTION

from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Ovenbird/lifehistory

The female clears a circular spot in forest floor litter and over the next 5 days weaves a domed nest of dead leaves, grasses, stems, bark, and hair. The nest’s squat oval side entrance is hidden from above and generally faces downhill if the nest is built on a slope. The inner cup is just 3 inches across and 2 inches deep, lined with deer or horse hair. The outer dome, camouflaged with leaves and small sticks, may be up to 9 inches across and 5 inches high. Its resemblance to an outdoor bread oven with a side opening gives the Ovenbird its name.

Egg Description: White with reddish-brown spots and speckles.

I, also, find this description, from the same website, absolutely adorable:

By day 8, the chicks leave the nest one at a time, with several hours between the first and last. As they run and hop away from the nest, the parents split the brood. The male keeps his young within the territory, and the female leads hers to an adjacent area. Females feeding young in neighboring territories are not harassed. The chicks need several more days to begin to fly, and don’t become independent until around day 30. Immature Ovenbirds spend time feeding and “playfully chasing” other immature birds, who may or may not be from the same brood. They remain on the breeding grounds until after adult males and females have started their separate migrations in the fall, then they too set off.

Jonathan’s remarks about finding this nest:

My friends and I have been practicing leaf litter trailing every weekend for the past month. On Sunday, right after we lost a hot deer trail, we found an Ovenbird nest! I’ve looked hard for them before, but never seen one—they’re sooo camouflaged. The only reason we spotted this one was that it was in a little clearing with grassy substrate.

The egg was laying about 12″ to the side, and we moved it to the front for the photo. It appeared to have been predated, with an uneven hole along the long side, no evidence of the membrane folding back inside, and a small hole next to the larger hole, perhaps made by an incisor or canine tooth.

I think the small hole may have been a beak mark from an avian predator. There is a larger hole on the other side, the jagged edges of which are just barely visible on the bottom of the egg.

Tracker Tuesday, July 21, Bird Tracks and Signs

Our question today comes from Ngala Training Camp in the Greater Kruger area of South Africa. Who’s track, and why?

The left foot’s track from an ostrich, photo by Kersey Lawrence.

I guess this one was too easy, but it was fun, and just too perfect a track to pass up! We have never seen ostrich on the side of our reserve where our camp is, so, one day recently when we drove out, I was shocked to see these from my perch on the Tracker’s seat. I tried to make them into partial hippo tracks, but couldn’t, and quickly came to the realization that we had been visited by the “six-foot, Kalahari racing chicken.” I immediately told Phil to stop the car, and turned around to Lee and said, “There are ostrich tracks in the road!” His eyes, grew wide(r), and we all piled off the vehicle to oogle and photograph them. We tried to find the bird, but his tracks were on almost every road – he’d walked that reserve flat, probably looking for more of his people.

Our answers were:

munro_wildlife (Peter Walker-Munro, UK) Nice ostrich, very fresh as definition is still in the track of the pad. Two toes and one nice claw.

foxtracker805 (Mike Watling, California, USA) I concur w/ostrich. Two prominent toes; one large w/a claw and a smaller outside toe. This the left foot. A unique bird track.

johan.vanrooyen.1272 (South Africa?) Awesome track, love the fine print inside it. Also think it’s an Ostrich, two toes leads to bird, one long big toe, not sure if there is another bird in Kruger with that size big toe, the claw on big toe and then the smaller side toe. Also thinks it’s left print.

Sandy Reed (Ohio, USA) – Huge toe with claw, and the side toe. And the texture in the track.

Dan Gardoqui (Maine, USA) – The Big Bird of Southern Africa.

Justene Tedder (Canada, formerly South Africa) – The two-toed bird!!!

Chuggy Charles (UK) – Too easy. It’s a left foot of a Struthio camelus. One large toe with a big claw mark out front, with a smaller second toe in the print, to the side – small toe is on the outside of the foot, hence it’s a left foot. Not sure if it’s fore or hind though…

Very funny, Chuggy! (LOL)

Tracker Tuesday, July 28, Mammal Tracks and Signs

Who’s track, and which foot is it from? From Wisconsin in the USA.

The left hind track of a raccoon, photo by Kersey Lawrence.

Our answers were:

Denis Warburton (Canada) – Left front track, Procyon lotor. Why, because the toe on the right is the shortest, like our thumb.

Sandy Reed (Ohio, USA) – Five fingers, looks like a few claw marks, perfect “little hand” with arched pad. Nice “thumb” on the right. Agree with Procyon lotor, front left.

belgianwildlifetracker (Soren Decrane, Belgium) – Raccoon, left front?

foxtracker805 (Mike Watling, California, USA) – Left front Raccoon. Long cigar shaped toes; drop down toe 1; toes 3&4 are on a flat spot on the pad; pad thickest on outside.

alexbinfordwalsh (Alex Binford Walsh, Arizona, USA) – I was going to say raccoon right front. But foxtracker is making me think left. Front foot because of the smallish pad compared to what a back pad would be. Left because the larger “thumb” is on the inside.

johan.vanrooyen.1272 (South Africa?) – Never seen a racoon in real life, but interesting track.

quinrutherford (Quintin Rutherford, South Africa) – Raccoon, left back foot? Left because of the positioning the toes and back because of the outside right toe sitting wide and close. Wild guess.

Soooooo…. I agree with everyone on raccoon (those five long, cigar-shaped toes, that are well-connected to the metatarsal pad), and a left track, but I think this is a hind track, which would make Quintin’s answer correct!

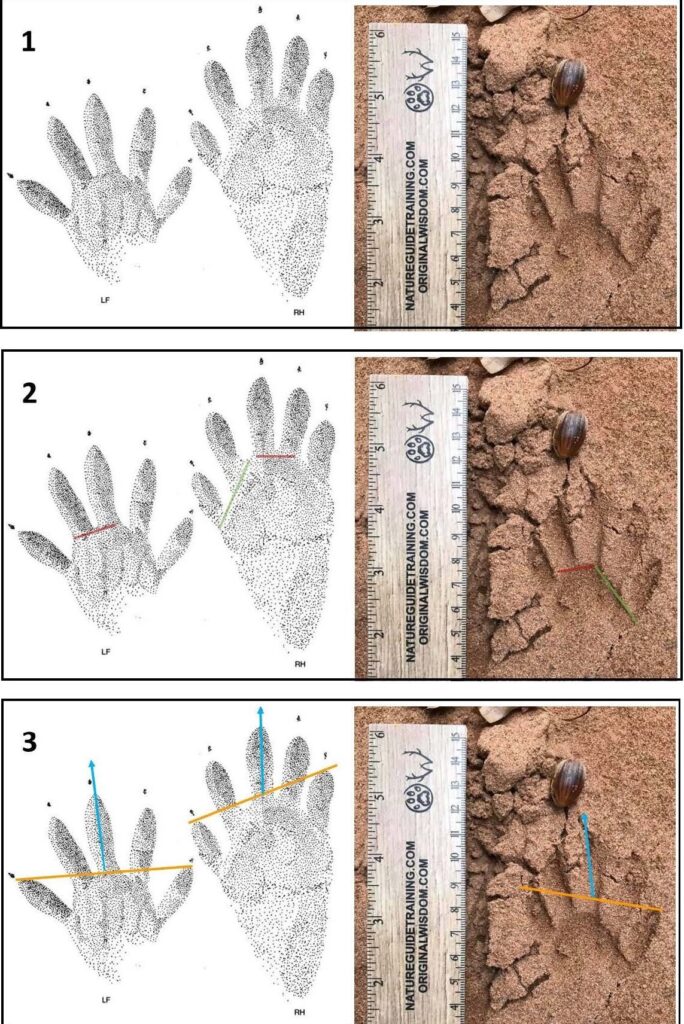

Take a look at the sketches below, from Mark Elbroch’s Mammal Tracks and Signs A guide to North American Species, (2nd ed.), next to our photo, and let’s work through this together.

The sketches above are side by side with the photo of the track. There are three rows, labeled 1, 2, and 3, cleverly enough. Row 1 is an unmarked comparison, so you can see all the features, without markup. Mark has drawn a left front foot next to a right hind foot.

Row 2 has a green line and a red line drawn in. The red line is way to tell left from right, especially when combined with the observation that toe 1 appears “dropped down” in the track. There are typically two toes that almost join together at the base where they meet the meta-pads. That’s toes 3 and 4 (we number from toe one, always on the inside, and count up as we go around and out). So, whichever side these two paired toes are on, that’s the side of the body. That makes the photographed track a left track, because toes 3 and 4 are closest to the outer edge of the track. Additionally, that long, sharp angle marked by the green line is present along the inside edge of the hind foot, making this a left.

Let’s observe more evidence for a hind track in Row 3, which has an orange and a blue line drawn in. The orange line is drawn across the top edge of the outer two toes, and the blue line is the angle of the middle three toes. We can see immediately that the front foot is much more symmetrical, meaning that if you drew a line down the middle of the track, from top to bottom, both sides would almost be a mirror reflection of the each other. The blue line is almost perpendicular to the orange line on the front track. On the hind track, however, the line comes off at a stronger angle.

I hope all that makes sense. Please feel free to comment and let’s discuss it further if you don’t understand or you aren’t convinced. It will help me to learn how to explain it better!

Tracker Tuesday, Aug 18, Mammal Tracks and Signs

Who shat that scat? In the Lowveld, South Africa!

Spotted hyena scat and tracks, photo by Kersey Lawrence.

Justene Tedder (Canada, formerly South Africa) – Spotted hyena! The half-moon shaped outer toes on the track – and the whitish colour to the larger, monogastric-type feces.

Justine further explained monogastric, after Kim Cabrera asked the obvious (and excellent) question – how can you tell? Justine, who is a veterinarian, said: The feces have none of identifiable contents and the colon is able to solidify them into these typical shapes for the monogastric animals – they chew their food well and the acid in the stomach does a good job. I could have elaborated carnivore monogastric as there are no colours or bits of plant/fruit that can sometimes be in the scat, like in primates or pigs – but that fibre for omnivores does change the shape of the feces from this scat!

Pete Fletcher (UK) – Ah beaten to it. I’d have said spotted hyena due to the white colour caused by the very high calcium diet.

johan.vanrooyen.1272 (Johan van Rooyen, South Africa?)Spotted Hyena?

rae.mcmurtrie (Rae McMurtrie, South Africa) Spotted hyena. Size and colour, spoor. Front foot on left bigger thank back foot on right, 4 toes on all feet.

andrewluc93 (Andrew Luciano, USA) Hyena? the shape, calcium buildup and little hairs? And the paw print. the right paw mark mingles with the other one. Doesn’t Hyena paws curve a little on the right side?

I wasn’t quite sure what Andrew was describing about the curve of the paws on the right side, but hyena tracks are asymmetrical, meaning that if you drew a line down the middle that one half would not be a mirror image of the other. And these are spotted hyena tracks, alongside a spotted hyena scat. We came along these when they were fresh, so there was no doubt about it. For all the reasons everyone said, above.

Scat, unless it is in a “classic” configuration, is highly questionable in my opinion. Wild animals eat a wide variety of things, and their health also varies. The presence of tracks that are the same age (and the absence of other tracks) are good confirmation.

Tracker Tuesday, Aug 25, Mammal Tracks and Signs

A large bone, bleached from the sun, laying in a road here in South Africa… why?

A large bone, carried and dropped by an elephant into a road in South Africa, photo by Kersey Lawrence.

A lot of animals eat bones for the calcium content, but only a few can carry one this large. And why carry it, at all, if you are going to eat it? Why not just eat it where you stand? That’s what most animals do. I’ve seen many giraffe and other ungulate species osteophaging (eating bones) for the calcium. I once had the pleasure of calling in, over the radio on game drive, the odd incidence of a “giraffe eating a buffalo.” It was osteophaging.

But, elephants seem to carry the bones of other elephants for no reason. We have often observed them stopping at the carcass of another elephant. Maybe they knew the other during its life? We don’t really know. We had traveled this road the night before, and no bone. The next day, this big bone in the road – and elephant tracks. They seem attracted to them.

Another question, of “do elephant graveyards exist?” (A mythological place where elephants go to die, and lots of their bones are found in one area), has been answered. The answer is no, not really. Elephants only have six sets of teeth in their lifetime. When one set wears out, a new one replaces it, until the last one wears out. When that happens, they need to go someplace where the food is soft so they can chew it. These areas are often along rivers and large bodies of water, with emerging vegetation. There, they gradually lose body condition until they succumb. Over time, many elephants will die in the same area, and we find their bones, particularly their skulls, resulting in the myth of elephant graveyards.

Thanks to everyone who participated. Let’s keep learning together! If you have photos (with an explanation that you’d like to contribute), please contact me at kersey@originalwisdom.com – your contributions will be credited to you.

#TrackerTuesdays, #weeklytrackingchallenge, #trackingisoriginalwisdom, #natureguidetraining, #cybertracker, #trackercertification, #trackermentoring, #alwaystracking, #environmentaleducation, #ecologicalliteracy, #ecologicalintelligence #wildlifetracking, #animaltracking, #tracksandsigns, #systemsthinking, #ecology, #nature, #science, #conservation, #sustainability, #resilience, #adaptation #thinkinglikeamountain #weareallconnected #BeMoreNeedLess #trackinginafrica #greaterkruger,

Download our recommended reading list for trackers by signing up for our “News for Trackers” newsletter!

Our goal is NOT to be spammy with our newsletter. We’d just like to send occasional updates on upcoming programs and maybe some cool info on wildlife, people, and tracking!

Once the sign-up form has been submitted, you will be re-directed to the download page.

Download our recommended tracking book list (and some other resources). It’s specific to Southern Africa and North America, but, a good tracking book is helpful in any region as a starting point to learn how to look at track morphology and animal behavior.

[contact-form-7 id=”2892″ title=”Subscribe to the newsletter”]